Sent Back

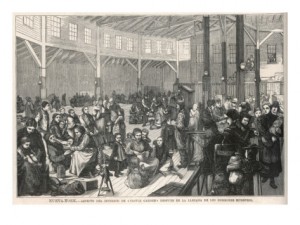

In the latter half of the 19th century, the principle role that New York City filled for Mormonism was as a transit point—more than 75,000 Mormon converts entered the United States through New York City during those years while several thousand missionaries sailed for Europe from New York’s port. But beginning with the Page Act in 1875 and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the U.S. began restricting immigration, beginning with Chinese and also including convicts, lunatics, and “others unable to care for themselves.” And in the late 1880s, attention on polygamy prosecution in Utah led to a provision of the Geary Act of 1892 which prohibited entry by polygamists. If you were restricted from immigrating, you were sent back.

In the latter half of the 19th century, the principle role that New York City filled for Mormonism was as a transit point—more than 75,000 Mormon converts entered the United States through New York City during those years while several thousand missionaries sailed for Europe from New York’s port. But beginning with the Page Act in 1875 and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the U.S. began restricting immigration, beginning with Chinese and also including convicts, lunatics, and “others unable to care for themselves.” And in the late 1880s, attention on polygamy prosecution in Utah led to a provision of the Geary Act of 1892 which prohibited entry by polygamists. If you were restricted from immigrating, you were sent back.

Diaries of Mormon immigrants and Church immigration records reflect the antipathy towards Mormon immigration in the late 1880s. For example, when the Wyoming arrived on August 31, 1886 with 301 Mormon immigrants led by David Kunz among its passengers, the immigration agents scrutinized them carefully. In his diary, Thomas Sleight complains about the way the agents treated the Mormons, recording that “Our company was much annoyed by the government officers detaining some of our company through spite.”

The official record of the voyage records a bigger difficulty:

“Forty-five of the emigrants were detained there by Commissioner Stephenson of pretended charges of pauperism, but finally all were permitted to continue their journey, except a woman and three children who were sent back to England. “

I assume that the charge of “pauperism” referred to the requirement under the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act that immigrants be able to care for themselves. Of course, the Church’s immigration system cared for immigrants, at least until they reached Utah. I’m afraid I have no idea how well they received support after they reached Utah — but I suppose it depended on which ward they ended up in. But convincing the immigration agents that Mormons would not end up paupers in Utah was undoubtedly difficult.

I can’t imagine how the woman with three children who was sent back to England felt. I imagine it must have been extremely demoralizing, after working to get ready for the trip, hoping for a new home in Utah and traveling for 10 days on the Wyoming across the ocean. Today few immigrants have to face such difficulties.

I haven’t yet tried to figure out who this woman was was or what happened to her and her children. Why wasn’t she traveling with her husband? Was she a widow? Or was her husband an unbeliever? Did she try again later, perhaps obtaining enough cash and resources to convince the immigration authorities that she wouldn’t become a pauper? Did she stay in the Church?

Regardless, the antipathy towards Mormon immigrants increased until organized Mormon immigration ceased in 1890 and likely continued into the 20th century when Mormon immigrants, then traveling on their own instead of in organized groups, could be identified.

Its hard to say how much of this antipathy was due to anti-Mormon sentiment, how much was simply antitpathy towards immigrants in general and how much was just bureaucrats enforcing a racist law (i.e. the Chinese Exclusion Act) that congress had passed. Undoubtedly all of these and more was involved.

Perhaps we can gain a more compassionate view of our disputes over immigration policy today if we put ourselves in the place of this woman and imagine what it must have felt like to be sent back.

June 22nd, 2012 at 10:43 am

[…] on this post can be made on the Mormons in New York City blog.] Be the first to like. Like […]

June 22nd, 2012 at 1:44 pm

If the woman was deemed a pauper, how was her return fare paid?

June 22nd, 2012 at 1:52 pm

I have no idea. Perhaps the shipping line was obligated by the US govt to take her back, and then could try to get money from her after she was back? That would leave her with a debt to be paid.

June 22nd, 2012 at 1:54 pm

Some poignant and dramatic history, when you put yourself in the place of these immigrants. Thanks, Kent.

I haven’t tracked down this woman and her children (and perhaps one other — the news reports conflict in how many were ultimately sent back) by name, but apparently they made it to Utah anyway. The Deseret News reports late in October that they arrived back in Liverpool, were met by the LDS immigration people, and were put on another ship headed toward America. Because they were only a small handful, not the 301 Saints who had come together on the Wyoming, and because they didn’t announce their Mormon faith, they received no more scrutiny on arrival than any other passengers, and were allowed to land (after three ocean crossings!) and go on their way.

When the 45 passengers of the Wyoming were originally detained, the church lawyers’ case tried to make the real point (that they were not paupers, and would not be a drain on unwilling American citizens), but also relied on what most of us consider “technicalities.” There was an ongoing debate in New York courts about what “landing” meant — did immigrants have to be processed while still on board ship and detained then before their feet touched land, or, as was the case with the Wyoming’s passengers, did entering the port facilities at Castle Garden mean they had “landed” and that they were no longer subject to the restrictions placed on immigrants who had not yet landed? People hoped that this hearing regarding the Wyoming passengers would be the test case that finally settled that controversial question; apparently it was not, though.

Like you, I think we would have a lot more compassion for the plight of immigrants today, and the meaning of all sorts of laws regulating their immigration, if we remembered the treatment of our own honored ancestors in similar circumstances.

June 22nd, 2012 at 1:57 pm

And you’re right — the shipping company that brought passengers who were not allowed to land was obligated by law to return the rejected passengers to the port where they had boarded the ship.

June 22nd, 2012 at 2:00 pm

Then she would be a pauper.

June 22nd, 2012 at 3:04 pm

These days the law requires common carriers which bring people to the U.S. who turn out not to be admissible to return them back to their point of origin. My hunch is that the same rule would have applied back then–how else could the U.S. rid itself without cost of “undesirables.”

Whether the carrier then has a claim for the cost of the return passage depends on the local law of the point of origin. But I’d guess that most such claims would go unpaid.

June 25th, 2012 at 12:53 pm

Thanks for posting this. On the upside, there’s some empirical evidence that Mormons, on average, are more immigrant-friendly in their political preferences:

http://www.sltrib.com/faith/ci_12787629